Anyway, to business. *serious face* From the title of this post, you may have guessed that I'd be talking about Shakespeare today. In fact, I will be - although not for a couple of paragraphs yet - but the topic of this post will actually be a different kind of stage. Prepare yourselves, ladies and gentlemen, for one of the most intense experiences of my entire Year Abroad: the stage d'anglais oral.

|

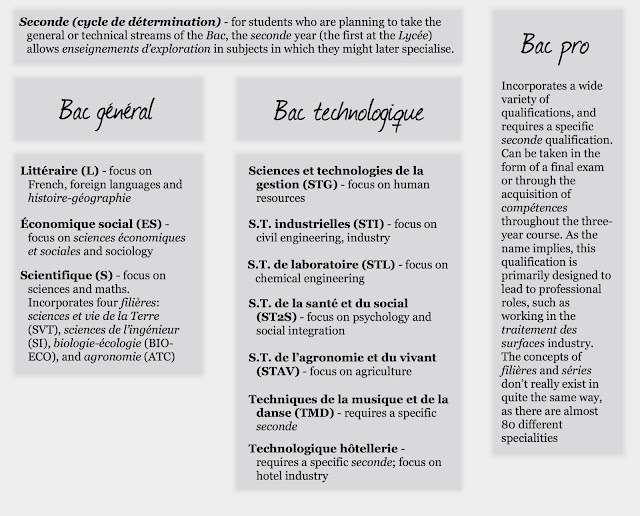

| (Fig. 1) Obligatory flashy picture produced by the Académie. |

As part of its égalité des chances (equal opportunities) programme, the Académie, or local education authority, runs a series of stages d'anglais et d'espagnol during the school holidays. The idea is to give students at a lycée the opportunity to develop their skills in a friendly, small-group environment, giving them a desire to communicate. Of course, in order to work, these events need people to run them; given as how the above description sounded pretty similar to what I've been doing as a language assistant this year, I thought I'd give it a go.

And so it came to pass that, on Monday morning, I arrived at a nearby lycée, ready and excited to work on delivering an engaging programme. Except there was just one problem - there was no programme. I'd turned up expecting to be given a series of worksheets to guide the students through, but as it turned out we were completely left to our own devices; this is understandably pretty scary when it's your first stage, it's 8am on a Monday morning, and you've got three hours to fill without any materials to hand.

Thankfully, since it was an extra-curricular event, there was no list of prescribed topics to cover, meaning that I could do more or less whatever I wanted. My plan came together over the course of a rather hectic Monday morning, and by extension Monday evening, so that by the following day I was able to deliver a pretty balanced programme to the (different) group that was waiting outside my door at 8am. More than that, it went rather well! On each of Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, I split the morning up into four 50-minute sessions, during which we focused on introductions, listening, conversation and discussion respectively. With that in mind, I present you with 'three-useful-things-that-Edward-used-in-a-frantic-attempt-to-fill-time-but-which-actually-worked-pretty-reasonably':

- Two truths, one lie. This is a great introductory game, and is also incredibly simple. Each student has to write down three pieces of information about themselves, of which two are true and one is invented. The other students then have to guess which one is which; for some reason, all my students thought that I had a brother called Xerxes but no-one believed that I played one of the Ugly Sisters in a panto!

- Alibi. A useful game to develop conversation skills. Students are split into teams of two, and have to invent an alibi that excuses them from a crime committed yesterday (say, a robbery at the supermarket down the road). Each one of them is interviewed individually, and the prize goes to the team whose stories have the fewest discrepancies. A sure-fire way to get some very detailed questions, fired off in an attempt to catch other teams out ...

- The shopping channel. A game that developed out of hot-seating. Upon realising that the standard technique of 'sit-in-a-chair-and-talk-about-this-object-for-30-seconds' was a bit too advanced for some of my students, I modified it slightly. Every student had to choose one object from their bag, which I then redistributed. After a minute or so of preparation time, each student then has 30 seconds to try and sell everyone else the object they've been given, in the spirit of a shopping channel. This can lead to some very unusual situations, such as 17-year-old young men having to sell nail files, but is always very funny when you put some happy-shopper music over the top of it.

Four days later, I can genuinely say that the experience of doing a stage was ... well ... unique. Extremely tiring, yes; teaching for four hours non-stop every day for four days is absolutely knackering. But it was also really fun, and allowed me to develop my teaching style while working with some really intellectually engaged students. My only concern is over my copious viennoiserie consumption during the week: my stomach probably hates me right now.

Oh, and I said I'd mention Shakespeare! Well, for our last lesson together, my secondes group had had to learn an extract from Romeo and Juliet (in modern English). I thought I'd get into the spirit, and so had a go too - although to make it fair, I had to learn the original stuff (for the interested, Act II, Scene 2, ll. 1 - 25). The students then marked me in the same way that I'd marked them, taking an immense pleasure in pretending to dock me marks for pronunciation. Talk about bad Juli-etiquette ...